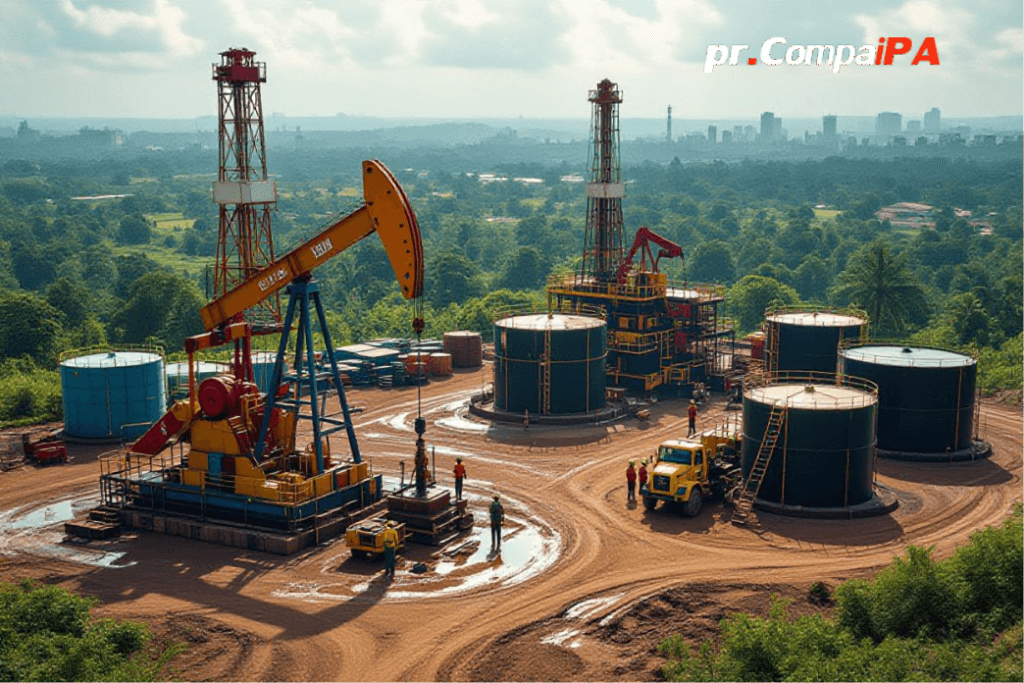

Nigeria unlocks Upstream Oil Growth Plan with 1.7m bpd Output and $20bn Projects

It’s kind of wild when you realize that while the world keeps shouting about divestment and renewables, you’re watching Nigeria quietly push its upstream oil game to about 1.7 million barrels per day. You’d think the pressure would slow things down, yet you’re seeing over $20 billion in planned field developments lining up, which signals that investors aren’t exactly walking away.

Key Takeaways:

- 1.7 million barrels per day sounds like just a number, but it shows Nigeria’s upstream oil sector is actually moving, not stalling, even with all the global turbulence in oil markets.

- $20 billion in planned field developments is a big signal to investors that Nigeria’s still very much in the game, lining up long-term projects instead of just squeezing old wells dry.

- Regulators at NUPRC are basically saying, “yeah, the world is shifting to renewables, but we’re still attracting capital,” which tells you policy and sector reforms are starting to land.

- Global oil majors trimming or exiting some Nigerian assets hasn’t killed the story; it’s just reshaping it, with more room for independents and local players to pick up the slack.

- That production level hints at some stability in operations and security, which, if you follow Nigeria’s oil history, hasn’t always been a given at all.

- Balancing upstream oil growth with rising renewable energy pressure means Nigeria’s trying to straddle two worlds at once, using current oil cash to stay relevant while the energy mix evolves.

- The overall vibe here is momentum-with-headwinds: not a boom, not a collapse, but a sector that’s grinding forward despite divestments, climate debates, and financing constraints.

What’s Nigeria’s Oil Output Really Looking Like?

The Numbers Behind 1.7m bpd

Imagine you’re running a portfolio review and someone tells you output is at 1.7 million barrels per day – sounds neat on paper, but you instantly want to know what sits behind that headline figure. In Nigeria’s case, you’re mostly looking at a mix of joint venture (JV) onshore and shallow water barrels, plus deepwater production that quietly does the heavy lifting. Deepwater fields like Bonga, Erha, Agbami, and Egina consistently deliver a big chunk of the liquids, often above 700,000 bpd combined when uptime is strong, while onshore JVs and independents fill in the rest along the Niger Delta grid.

What might surprise you is how much of that 1.7m bpd is actually “protected” by location and infrastructure design. Deepwater volumes are offshore, far from community disruptions and pipeline vandalism, and a good portion of the onshore crude now gets routed through dedicated evacuation systems like the Trans Escravos and Nembe Creek lines with tighter surveillance. You’re also seeing marginal field operators and indigenous players contribute 10-15 percent of total liquids, which matters because it means your exposure isn’t tied to just 3 or 4 majors – the production base is slowly getting broader, if not yet fully diversified.

Year-on-Year Growth and Trends

When you zoom out over the last 3 to 5 years, you see a pretty jagged production chart, not a smooth upward glide. Nigeria slipped below 1.2m bpd at one point in 2022 as theft, pipeline shutdowns, and underinvestment bit hard, then clawed its way back up with output recovering by 300,000-400,000 bpd in roughly 12-18 months. For you as an investor or industry watcher, that recovery pace matters more than the raw 1.7m number, because it tells you systems and interventions actually moved the needle, rather than the market just getting lucky.

A big part of that turnaround came from better handling of the hot spots: tighter surveillance on key trunklines, contracting private security for sensitive right-of-way sections, and rerouting some production through alternative evacuation options like barging and FPSO shuttle loading. At the same time, a few previously choked assets were brought back toward nameplate capacity as deferred maintenance was cleared. So if you’re comparing year-on-year, you aren’t just seeing more wells, you’re seeing lost barrels slowly coming back into the counted stream.

One thing you need to weigh carefully is how sustainable those trends are against your own time horizon. Output growth over the last year has leaned heavily on restoring legacy capacity rather than huge new greenfield volumes, which is fine in the short term, but eventually you want those $20 billion in planned field developments to show up in the data as fresh incremental barrels, not just recovered ones. The pattern you’re likely to see, if things hold, is a plateau around current levels, followed by step changes whenever a large deepwater project, a gas-liquids hub, or a brownfield infill campaign hits first oil, so your strategy should probably assume volatility quarter to quarter but a gently improving baseline if policy and security gains don’t unravel.

Why Are Huge Field Plans Worth $20bn?

Breaking Down the Investments

You can picture one of these new deepwater projects like a small floating city: FPSO vessel offshore, subsea wells spidering out on the seabed, miles of flowlines, power systems, digital monitoring, the whole works. That single “city” alone can swallow $5 billion to $8 billion before first oil, which is why the $20 billion headline number actually boils down to a handful of very big, very complex developments stitched together.

On top of that, you’ve got all the invisible-but-expensive stuff: front-end engineering design (FEED), 3D seismic, appraisal wells that might each cost $80 million to $120 million, local fabrication yards being upgraded so you can hit Nigerian Content targets, and long-lead items like subsea trees that have 24+ month delivery timelines. A single brownfield revamp onshore or in the shallow offshore can run into the $500 million to $1.5 billion range when you add gas handling, flare reduction, and new evacuation routes, so when NUPRC talks about $20 billion in the pipeline, you’re looking at a full value chain refresh – not just a couple of rigs drilling a few shiny new wells.

What This Means for the Economy

Imagine a fabrication yard in Lagos or Port Harcourt that’s been half-idle for years, suddenly getting work orders for topsides modules, manifolds, and pipeline spools tied to these new field developments. That kind of activity doesn’t just pay welders and engineers; it pulls in caterers, transporters, security outfits, small logistics firms, software providers – your entire local ecosystem starts to hum. When projects of this size move ahead, you’re effectively turning CapEx into widespread paychecks.

For you as a business owner or professional, it means more than just “oil money” flowing into the federation account. You’re looking at higher demand for housing in project hubs, stronger traffic for local banks and fintechs handling project payrolls, more work for legal and consulting firms, and a deeper pool of technical skills that can later be exported into other African markets. If output actually stabilizes around 1.7 million bpd while these $20 billion plans roll out, you’re talking stronger FX inflows, some relief on naira pressure, and a better shot at funding infrastructure outside oil – roads, power, even digital backbone – that directly shapes your daily operating environment.

On a longer horizon, you also get a more investable story to tell: when lenders and equity partners see sanctioned projects with clear reserves, defined timelines, and NUPRC-backed frameworks, they price Nigeria differently. That shifts your world, too, because sovereign risk feeds into the interest rates your company pays, how foreign partners view your JV proposals, and even how quickly you can close deals in adjacent sectors like gas-to-power or petrochemicals. In other words, $20 billion in the fields can quietly rewrite the cost of doing business in your own corner of the economy, whether you ever set foot on a rig or not.

Why Should We Care About Global Divestment?

The Impact of Divestment Trends

In one part of the world, you have funds dumping fossil assets as fast as they can; in another part, like Nigeria, you’re lining up $20 billion in new upstream projects and chasing 1.7 million bpd and beyond. That clash matters for you because global capital markets still set the rules of the game: who gets cheap financing, who pays a premium for risk, and who ends up stranded with assets nobody wants on their books. When large institutions controlling over $40 trillion in AUM have some form of ESG or climate policy, you’re not just reacting to a fad; you’re dealing with a structural re-pricing of oil and gas risk.

Instead of thinking of divestment as a distant “Western” policy debate, you should see it as something that can quietly raise your cost of capital by 200-400 basis points, shorten your project timelines, and force you into tighter offtake and decommissioning terms. If lenders expect a shorter oil demand peak window post-2030, they push for faster payback and tougher covenants, which hits complex Nigerian projects hardest: deepwater developments, marginal fields needing enhanced recovery, and gas monetisation with long-value chains. So when global funds exit, you don’t just lose money, you lose optionality.

Are Investors Actually Pulling Out?

What often surprises people is that capital hasn’t evaporated; it has just become choosier and a bit more skittish around long-life hydrocarbons, especially in frontier or “governance-risky” jurisdictions. You see European majors like Shell, BP, and TotalEnergies talking up renewables and portfolio high-grading, while quietly offloading mature onshore and shallow-water assets in the Niger Delta to local independents – that’s not a total exit from Nigeria, it’s a strategic reshuffle, but it absolutely changes who you sit across the table from. At the same time, US majors and some Asian NOCs still commit to deepwater and gas-led projects, but they’re demanding clearer regulatory signals and faster approvals from bodies like NUPRC to justify the spend.

If you zoom out beyond the headlines, the data is more nuanced than the “everyone is divesting” narrative. Global upstream investment is still projected in the $500-550 billion per year range to 2030, yet a bigger share is flowing into lower-cost, lower-carbon-barrel plays in places like Guyana, Brazil, and the Middle East. That means Nigeria is not being abandoned, but you are competing with jurisdictions that can show faster cycle times, better security outcomes, and clearer fiscal terms – and when investors have that choice, they will quietly reallocate capex without making a big public fuss about divestment campaigns.

On top of that, you now have a split investor universe: some pension funds and European banks have formal “no new fossil” rules, while others, like certain Asian lenders, Middle Eastern sovereign funds, and private equity pools, are actively hunting for the very assets being shed, especially where they see upside from operational fixes or brownfield expansions. So yes, some capital is walking out the front door, but a different kind of capital is coming in through the side entrance, often with higher return expectations, stricter performance conditions, and a sharper focus on issues like gas flaring, carbon intensity per barrel, and local content, which directly shape how you design, finance, and operate upstream projects in Nigeria.

Is Renewable Energy Really a Threat?

The Push for Clean Energy

In a lot of global boardrooms right now, solar, wind, and green hydrogen sound sexier than a deepwater appraisal well, and you can feel that in the way capital is being allocated. You see it in Europe’s REPowerEU plan targeting 600 GW of solar by 2030, in the U.S. Inflation Reduction Act, throwing hundreds of billions of dollars behind low-carbon tech, and in Asia chasing battery supply chains like they’re the new crude. For investors under ESG pressure, funding a 25-year oil project suddenly looks politically heavier than backing a 5-year renewables fund, even if the returns on oil are still very attractive on a pure numbers basis.

At the same time, you’re dealing with a pretty sharp reality check that many people outside the industry gloss over: renewables are scaling fast, but oil demand hasn’t fallen off a cliff, not even close. The IEA still has global oil demand hovering around 100 million bpd in the 2030s in several scenarios, and emerging markets – including Nigeria’s neighbors – are where a chunk of that growth or stickiness sits. So while climate targets are getting stricter, aviation, shipping, petrochemicals, and heavy transport still lean heavily on liquids, which means your upstream barrels, if low-cost and relatively low-carbon, are not obsolete at all; they’re actually more competitive in a tighter, more selective market.

The Push for Clean Energy

When you zoom into the policy details, it becomes obvious that “clean energy push” doesn’t automatically mean “no oil from Nigeria”. It means higher scrutiny. The EU’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism, rising carbon prices above 90 euros per ton in some periods, and net-zero pledges from over 130 countries are really telling you one thing: high-cost, high-emissions barrels will get squeezed out first. If your projects sit in the lower half of the global cost curve and can show lower methane intensity and flaring, you’re not the target; the marginal, dirty barrels are.

You’re also seeing big integrated companies play a hedged game: TotalEnergies, BP, Shell, and others are divesting some onshore and shallow-water assets in Nigeria while ramping up renewables in Europe and Asia, yet many of them are doubling down on advantaged deepwater or gas projects where fiscal terms and emissions profiles look better. So instead of reading “energy transition” as a death sentence, you can treat it as a sorting mechanism that separates sloppy, inefficient operations from lean, well-managed portfolios that can survive $50 oil and tighter carbon rules. That’s actually where your opportunity sits.

How Nigeria’s Oil Sector is Coping

On the ground, your response has been less about panic and more about pivoting, sometimes quietly, sometimes very loudly. You’ve got the Petroleum Industry Act reshaping fiscal terms to pull in long-term capital, while the NUPRC keeps repeating that about $20 billion worth of new field developments are already in the pipeline, even as global majors rebalance their portfolios. That doesn’t happen by accident; it happens because projects with better breakevens and clearer regulatory frameworks still look bankable to lenders, private equity, and even some cautious IOCs.

At the same time, a lot of operators are rebranding their story from “we produce oil” to “we produce lower-carbon energy” and backing it up with specific moves. You’re seeing more associated gas being monetized through domestic gas-to-power, fewer routine flares as NUPRC tightens enforcement, talk of CCS pilots, and marginal field operators clustering infrastructure to cut costs and emissions per barrel. In practical terms, the sector is trying to stay investable by proving it can cut leaks, flaring, and downtime while keeping lifting costs competitive, so your barrels sit in that club of “transition-resilient” supplies that financiers and offtakers still want in their portfolios.

Dig a bit deeper, and you notice how coping has become quite tactical: some indigenous players are snapping up divested onshore assets at discounts, then sweating those assets harder with better community engagement and lower overheads, while others are leaning into gas as the “transition fuel” tag opens up funding windows from development banks that would shy away from pure oil. You also have JV restructuring to reduce cash-call bottlenecks, more use of alternative financing like reserve-based lending, and operators bundling ESG upgrades – like leak detection, digital monitoring, and solarizing flow stations – into field development plans so they can tick investor boxes without killing project economics. All this might feel incremental when you’re in the weeds, but stacked together, it’s how your upstream sector stays in the game even as the energy transition narrative gets louder every quarter.

My Take on Nigeria’s Upstream Sector Resilience

You care about this sector because your cash flow, lending book, or policy targets live and die on whether barrels actually get produced, lifted, and paid for, not on glossy strategy documents. What stands out right now is that despite global divestment pressure and the steady drumbeat of energy transition narratives, Nigeria is still pushing out around 1.7 million barrels per day and lining up roughly $20 billion in new field developments – that tells you something about staying power. And if you drill down into the NUPRC data, you see a pattern: projects that were written off as stranded a few years ago are quietly moving into appraisal and development because investors finally see regulatory and security risks getting a bit more predictable, not perfect, just bankable enough.

What you should really be weighing is the quality of this resilience. Are you looking at a short-lived production bump or the early phase of a more disciplined upstream cycle driven by better cost control, smarter fiscal tweaks, and targeted infrastructure fixes like evacuation routes and crude handling upgrades? Because when operators start locking in lower unit operating costs, cleaning up measurement and metering losses, and pushing out produced water handling bottlenecks, you get resilience that actually survives low-price cycles. Perceiving that difference between noisy headlines and structural change is what will shape whether your next upstream bet in Nigeria pays off or drags you into another round of write-downs.

Factors Driving Growth

At the center of the growth story, you have a mix of regulatory clean-up, pragmatic commercial terms, and very old but very productive rocks that still flow if you treat them right. The Petroleum Industry Act (PIA) may not be perfect in your view, but it finally gives operators a clearer line of sight on fiscal terms, host community obligations, and license conversion paths, which is why you now see more aggressive timelines on marginal field tie-backs and brownfield workovers. Pair that with NUPRC’s tighter grip on flare gas commercialization, metering audits, and production optimization programs, and you start seeing incremental barrels show up from fields that had been technically alive but commercially asleep.

On the corporate side, the much-discussed IOCs-to-indigenous asset transfers are reshaping who spends what and where. You now have local players that understand terrain, community expectations, and logistics far better, taking over mature onshore and shallow water acreage, then squeezing more out of them via infill drilling, artificial lift optimization, and cheaper well interventions. Perceiving how these players leverage nimble decision making, local service capacity, and lower overheads gives you a hint at why production is climbing even as some majors quietly exit.

- Regulatory clarity under the PIA creates more predictable project economics.

- Indigenous operators revitalizing mature onshore and shallow water assets

- Increased brownfield investments, infill drilling, and workovers are boosting recovery

- Security improvements and better community engagement, cutting downtime

- Focus on cost discipline and operational efficiency to improve margins

- Gas commercialization and flare reduction are opening new revenue streams

- Improved evacuation infrastructure, reducing losses and export bottlenecks

- Perceiving structural rather than purely cyclical drivers behind current output gains

Looking Forward

Looking ahead, you should be testing every optimistic forecast against three filters: security stability, execution capacity, and contract sanctity, because those are the levers that will decide whether the $20 billion pipeline of planned projects actually reaches first oil or just stays as nice PPT slides. If Nigeria sustains current reforms, keeps calibrating fiscal terms to stay competitive with places like Angola and Guyana, and really backs indigenous players with access to project finance and technical partnerships, then your 5 to 10 year view can realistically include higher sustainable production, more gas-to-power volumes, and deeper local content in services. Perceiving the next phase as a window to lock in long-dated positions – before capital gets more expensive and ESG thresholds tighten again – might be the edge that separates you from everyone else still waiting on “perfect” policy signals.

The Real Deal About NUPRC’s Role

You probably don’t expect a regulator to be one of the main drivers of output growth, but that’s exactly what you’re dealing with here. Instead of just issuing licences and writing memos, NUPRC has been sitting in the middle of field development plans, unlocking over $20 billion in project approvals and pushing operators to move from paper to first oil a lot faster than they used to.

In practical terms, your upstream project now runs into a regulator that tracks everything from flare volumes to reserve replacement ratios, not just royalty payments. So when you see production creeping toward 1.7 million bpd, it’s not only because operators drilled more wells – it’s also because NUPRC forced better reservoir management, tighter production reporting, and a tougher stance on dormant assets that were just sitting on acreage without delivering barrels.

How They’re Supporting Progress

What catches most people off guard is how operational NUPRC has become in your day-to-day planning cycle. You’re getting clear field development plan timelines, standardized templates, virtual technical sessions, and sometimes joint reviews that shave months off approvals that used to drag on indefinitely, and that time saved translates directly into earlier cash flow and quicker payback on those multi-billion-dollar projects.

On top of that, the Commission is quietly nudging you toward lower unit operating costs and higher recovery factors through its technical audits. That might feel like pressure in the short term, but it opens the door to marginal field tie-backs, small-scale gas projects, and fast-track brownfield expansions that wouldn’t fly under old economic assumptions. For you, that means more flexibility: you can re-scope projects, stage your capex, and still stay aligned with a regulator that’s clearly signaling it wants barrels on stream, not just policy on paper.

What’s Next for Regulation?

What you should really be watching now is how NUPRC will pivot from just increasing volumes to tightening the screws on how those volumes are produced. You’re already seeing it in the Commission’s push for measurable emissions tracking, stricter gas flare penalties, and mandatory gas commercialization plans built into new field approvals, which means your next project won’t get a free pass if it treats associated gas like an afterthought.

At the same time, don’t be surprised when regulations start linking your licence security to performance on things like community engagement, asset integrity, and local content. The direction of travel is pretty clear: if you want long-term certainty on your acreage, you’ll need to prove you’re not just chasing short-term barrels but actually building resilient, lower-carbon, conflict-free operations that can survive whatever global transition throws at you.

Digging a bit deeper, you can expect NUPRC to roll out more integrated digital systems so your production data, flare data, and reserve reports are all visible in near real-time to the regulator, and that kind of transparency will change how you plan downtime, schedule maintenance, and negotiate with partners because inconsistencies will be called out quickly. There’s also growing talk around risk-based supervision, where “high-risk” fields – old infrastructure, security hotspots, high flaring – will face tighter oversight and more frequent inspections, while compliant assets get lighter-touch regulation, so if you invest early in compliance, ESG reporting, and cleaner technologies, you won’t just tick a box, you’ll probably secure a more predictable regulatory environment and better negotiating power when you push for new project terms or extensions.

Summing up

As a reminder, think about the last time you saw a headline claiming oil majors were packing up and racing toward renewables, and you quietly wondered where that leaves producers like Nigeria. What you’re seeing now – 1.7 million barrels per day flowing and about $20 billion in planned field developments – is your cue that the story isn’t about decline, it’s about adaptation. You’re dealing with a sector that’s learning to operate under tighter global scrutiny, shifting investor sentiment, and all the ESG talk, yet it’s still finding ways to attract capital and keep projects moving.

When you zoom out, your big takeaway should be pretty simple: you’re operating in a world where oil isn’t vanishing tomorrow, but it is getting harder to justify unless it’s efficient, transparent, and profitable. If you’re planning strategy, policy, or investment around Nigeria’s upstream space, you’re not just betting on barrels; you’re betting on your ability to navigate regulatory reforms, divestments, and the long pivot toward cleaner energy. And if NUPRC can keep translating these production gains and field plans into sustained output, you’ll have a stronger platform to fund your own transition story, instead of having it dictated to you from the outside.

FAQ

Q: Why does 1.7 million barrels per day actually matter for Nigeria right now?

A: Hitting about 1.7 million barrels per day (bpd) is a big statement that Nigeria’s upstream sector isn’t flat on its back like some people think; it’s a sign that production is stabilizing after years of outages, theft issues, and under-investment. When output climbs back toward OPEC quota territory, it means more export revenue, better FX inflows, and a bit of breathing space for government finances that have been under serious pressure.

A: For investors, that 1.7m bpd number says something else too – fields are actually being maintained, new wells are coming online, and infrastructure problems are at least being managed, not ignored. It’s not just a vanity metric; it’s a kind of health check that tells you the reservoirs are still productive, operators are spending money, and the regulator is getting more serious about tracking volumes and plugging leakages.

Q: What exactly is in this $20 billion upstream field development plan the NUPRC is talking about?

A: That $20bn figure is basically a basket of planned projects – new field developments, brownfield expansions, infill drilling, gas monetization projects, and key infrastructure upgrades like pipelines and processing facilities. You’re looking at a mix of deepwater projects, more marginal fields moving toward first oil, and some gas-focused developments that tie into Nigeria’s push to use gas as a transition fuel.

A: It won’t all land at once, of course, a lot of it is phased over several years with different final investment decision (FID) timelines. Think of it as a pipeline of opportunities: once fiscal terms, security, and commercial frameworks line up for each project, that piece of the $20bn story starts to move from “plan” to real steel in the ground and extra barrels or cubic feet on the books.

Q: How is Nigeria attracting investment while big oil companies are divesting from some onshore and shallow water assets?

A: The divestments you’re seeing from the supermajors aren’t a simple “we’re out of Nigeria” exit; it’s more of a portfolio reshuffle from onshore/shallow water into deepwater and other global priorities. Those onshore and shallow water assets are largely being picked up by independents and local companies that actually specialize in squeezing more value out of mature fields, dealing with host communities, and running leaner operations.

A: On top of that, NUPRC has been tweaking fiscal terms, clarifying regulations under the Petroleum Industry Act (PIA), and pushing for faster approvals, because investors really hate red tape that drags on for months. So while one set of players is trimming exposure, another set is quietly stepping in, and the regulator is trying to make the transition smoother so production doesn’t fall off a cliff during ownership changes.

Q: With global pressure for renewables, why are companies still interested in Nigeria’s upstream sector?

A: Even with all the talk about solar, wind, and EVs, the world still burns a lot of oil and gas, and that demand doesn’t disappear overnight; it tapers over decades. Nigeria’s barrels are relatively low-cost compared to some frontier plays, and when you’re a company trying to stay profitable during the energy transition, cheap-to-produce barrels look very attractive.

A: There’s also the natural gas angle that doesn’t always get the spotlight – Nigeria holds huge gas reserves, and gas is being positioned as a “bridge” fuel for power, industry, and export (LNG). So while investors are under ESG and climate pressure, many of them are shifting into gas-heavy portfolios, lower-carbon barrels, and projects where they can show better emissions performance rather than just slamming the door on hydrocarbons altogether.

A: Because of that shift, assets that can tie into gas-to-power, LNG, or petrochemical value chains get extra attention in Nigeria, since they tick both the money box and the “transition narrative” box at the same time.

Q: What role is NUPRC actually playing in this progress, beyond just releasing nice-sounding statements?

A: NUPRC’s core role is to regulate and monitor the upstream sector, but in practice, that means a lot of unsexy work like tracking production in real time, enforcing metering rules, clearing project approvals, and making sure operators stick to field development plans. The commission has been pushing for more transparency on volumes, flare data, and reserves, which helps reduce revenue leakages and makes the numbers more reliable for both the government and investors.

A: There’s also a strong push around reducing project cycle times – getting seismic, drilling, and development plans approved faster so projects don’t sit idle on someone’s desk for half a year. If NUPRC can keep that momentum, it becomes a bit of a partner for serious investors instead of just a hurdle, and that’s a big behavioral shift for a sector used to slow, painful bureaucracy.

Q: How are security issues and oil theft affecting Nigeria’s 1.7m bpd progress?

A: Production hitting 1.7m bpd is happening despite persistent security and theft problems, not because those issues are completely solved. Pipeline vandalism, illegal taps, and community-related disruptions are still a drag on volumes, especially in the Niger Delta, and they force companies to spend more on surveillance, alternative evacuation routes, and community engagement.

A: At the same time, government and private security initiatives, better surveillance tech (like drones and fiber optics), and more collaboration with local communities have closed part of the gap that used to bleed a lot of barrels daily. It isn’t perfect, but you can tell something’s changed when export terminals report higher receipts and companies feel confident enough to sanction new projects backed by more realistic production assumptions.

Q: What does all this – 1.7m bpd and $20bn in plans – actually mean for Nigeria’s long-term energy transition?

A: Short term, it means Nigeria wants to monetize its oil and especially gas resources more aggressively while global demand is still strong, using that revenue to stabilize the economy and ideally to fund infrastructure and diversification. Long term, the real test is whether the government uses this upstream momentum to build out gas-to-power, renewables, and industrial capacity, rather than just repeating the old “oil money, no structural change” cycle.

A: If upstream growth is paired with serious investments in gas infrastructure, grid improvements, solar projects, and local manufacturing, then this phase becomes a pivot point, not a dead end. If not, Nigeria risks being stuck with stranded resources and an economy still overexposed to a commodity that could face weaker demand and tougher climate policies down the line.

For deeper insights into related trends, explore our detailed analysis in a similar article.

Kick-start your tailored Financial PR campaign today—elevate your visibility, strengthen credibility, and shape the narrative before others do. Fill out your choice campaign that fits your financial PR strategic direction –

Brand Brief PR Campaign Plan Form

Financial PR Narrative, Amplified Form, and

The Corporate Intelligence Exchange Newsroom Form

Act Now!

This report has been thoughtfully developed to broaden readership and provide competitive economic interpretation by Adebola Adeola, CEO of Dinet Comms and Owner of PR CompaiPA, a Financial PR Agency.